Where did Austin Powers get his so-called mojo—that grooviness, that charm, that goofball sex appeal? He got it from his movies’ music. And he got his movies’ music from Quincy Jones, the legendary composer and hitmaker who brought us Thriller, “We Are the World,” and so much more.

How do I know? Austin himself shares as much in Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002), the third and final film in the Austin Powers franchise. Jones makes a cameo midway into the movie’s opening credits, conducting an orchestral rendition of his 1962 song “Soul Bossa Nova.” Austin points at Jones and tells us, “This is where the movie gets its mojo, baby.” Played by a Shrek-era Mike Myers, Austin then kisses Jones on the cheek. Jones exclaims, “Groovy!” Watch this scene in the video below.

Opening credits of Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002). Jones makes a cameo at 00:01:39.

The Austin Powers films dominated US popular media in the late 1990s and early 2000s. A spoof of the James Bond spy movies, Austin seemed to be everywhere at the time, his raunchy humor and over-the-top manhood inescapable. As a result, millennials like me know “Soul Bossa Nova” as the Austin Powers theme song. When hearing it, it’s difficult not to think of Austin whether we’d like to or not. But like all American music, the song’s history is richer than meets the ear.

Rewind to 1956. That year, Jones was directing jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie’s big band, which went on a tour of South America sponsored by the US government. The band was part of the “jazz ambassador” program of Cold War–era cultural diplomacy. On the tour’s Argentina stop, Jones met the pianist Lalo Schifrin. Schifrin went on to collaborate with Jones and during the tour turned him to bossa nova music. (He also told Jones about Nadia Boulanger, the distinguished teacher in Paris with whom Jones later enrolled in composition lessons along with Astor Piazzolla, Philip Glass, and other major figures). A slowed-down and jazz-infused form of samba, bossa nova had made a splash in Brazil, its country of origin. Brazil just so happened to be the next stop on the Gillespie band’s tour.

Bandmembers got to know Brazilian culture while traveling and performing in the country. On the side, Gillespie played in the rhythm section of a house samba band at a Rio de Janeiro hotel. Jones attended the gig, as did Astrud Gilberto, João Gilberto, and Antônio Carlos Jobim, each of them bossa nova pioneers. When “Dizzy threw his be-bop trumpet into the mix,” remembers Jones in his memoir, “that was the first time any of us had heard the fusion of jazz ’n’ samba. In fact, the song ‘Desafinado,’ by Jobim, feels just like a Dizzy solo.” The experience in Brazil inspired Jones to create his own bossa nova sound soon after the tour ended.

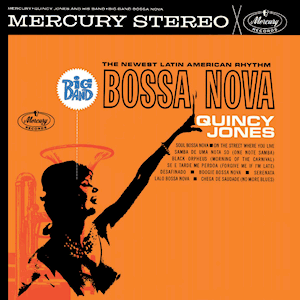

Jones composed, performed on, and recorded the album Big Band Bossa Nova in 1962. “Soul Bossa Nova” was the album’s first track. It is easy to hear Brazil’s influence on Jones in “Soul Bossa Nova.” Listen, for example, to the song’s bossa nova rhythmic groove and cuica percussion. “Soul Bossa Nova” combines such sounds with jazz, soul, and pop, genres that Jones became famous for in later decades. Yet there is something distinctly “1960s” about the song. It adopts a swingin’ stylistic mixture typical of the decade’s “bossa nova craze.”

Quincy Jones’s Big Band Bossa Nova (Mercury Records, 1962)

After its 1962 release, Jones ensured that “Soul Bossa Nova” would not go into hibernation. Instead, he and others gave new life to the song through other media—notably movies. It is easy to forget that Jones not only pioneered so much of the day’s popular music, but composed film music as well. Jones recycled “Soul Bossa Nova” in his score for 1964’s The Pawnbroker, directed by Sidney Lumet and starring Rod Steiger. Additionally, composer Marvin Hamlisch arranged “Soul Bossa Nova” in 1969’s Take the Money and Run, a mockumentary starring Woody Allen. The song appeared in Bob Fosse’s Sweet Charity in the same year. The dance resonances between Sweet Charity and Goldmember are hard to miss. Just check out the video below.

Dance sequence in Sweet Charity (1969)

Jones’s “business savvy was a key component of his success and longevity,” observes entertainment writer Jeremy Smith. “Rediscovery was as important as discovery.” This helps to explain the reappearance of “Soul Bossa Nova” not only in films, but on television, too. In Canada, the CTV network picked up the song as the theme music for Definition, a game show that IMDB describes as “a cross between Hangman and Scrabble.” It’s “very similar to ‘Wheel of Fortune’ without the wheel.” The show lasted from 1974 to 1989, when it caught the attention of a young Mike Myers, who grew up in the Toronto suburbs. “It’s one of those songs that captured an entire era,” Myers has reflected. Embodying ’60s-era kitsch, “Soul Bossa Nova” offered Myers the perfect music for a ’60s-era spoof about a secret agent man.

An episode of Definition from the mid-1980s. Listen to the opening thirty seconds for the show’s adapted use of “Soul Bossa Nova.”

In 1990, Jones served as a guest host on NBC’s Saturday Night Live, where Myers was a cast member. Jones and Myers developed a friendship while on set. They even prepared a sketch together (it was scrapped). So, Jones was happy to say yes when Myers contacted him for permission to use “Soul Bossa Nova” in the first Austin Powers film.

Ever since, “Soul Bossa Nova” has become inseparable from Austin. But the song’s story does not end with him. Even before Austin came along, hip-hop duo Dream Warriors sampled “Soul Bossa Nova” in “My Definition of a Boombastic Jazz Style” (1990). Ludacris sampled it in “Number One Spot” (2004). Jones himself revisited the song when he produced jazz artist Nikki Yanofsky’s “Something New” (2014). FIFA enlisted the song as theme music for the 1998 World Cup. The German comedy show Was guckst du?/Guckst due weita! employs the song as well. The list goes on.

Nikki Yanofsky, “Something New” (2014)

Clip from Was guckst du?/Guckst du weita!

Music is always on the move. It travels far and wide, endowing times, peoples, and places with its mojo. The idea of mojo itself as moved (and been obscured), originating as it did in African American Hoodoo and related spiritual practices. If we listen closely, “Soul Bossa Nova” has something to say about jazz history, cultural diplomacy, globalization, Brazilian music and culture, film music, television, retro nostalgia, and more. The song is an earworm, catchy. Beyond that, few of us have given “Soul Bossa Nova” much thought. It’s the silly “Austin Powers song,” plain and simple, right? There’s more to the story, if we just care to listen.

Jordan Musser is Managing Editor of publications at the American Musicological Society. He provides centralized editorial support, management, and volunteer coordination for all of the Society’s print and digital publication volumes, periodicals, and projects. Jordan has published his research in the Journal of the Royal Musical Association, the Journal of the American Musicological Society, Twentieth-Century Music, and other forums.

Learn more about this topic:

Check out Quincy Jones’s memoir

Read this short article about the “bossa nova craze”

Explore another take on “Soul Bossa Nova” in Austin Powers