When you picture the Wild West, you might start with a lone cowboy riding off into the sunset backed by a majestic Ennio Morricone score. Or maybe you think of the tinkling of a twangy piano in the corner of a dusty saloon. You’re not wrong to bring these images to mind. They’re pervasive, served to us on a platter of Hollywood glitz and ruggedly handsome heroes. But in reality, these sounds weren’t part of the historic West’s landscape. To understand what the West really sounded like we can follow the life of one of its noisiest residents: Mary “Bloody Knife” Porter.

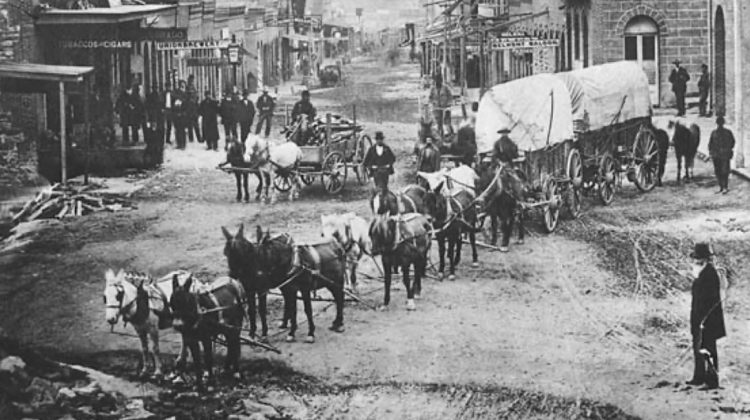

Born to sharecroppers in Kentucky, Mary Porter made her way westward in the late 1870s. Like many African Americans moving westward at the time, she was chasing the promise of emerging industries: the railroad, the mines, and the businesses that accompanied them. By 1880, she settled in Helena, Montana.

Ten years later, she had become notorious.

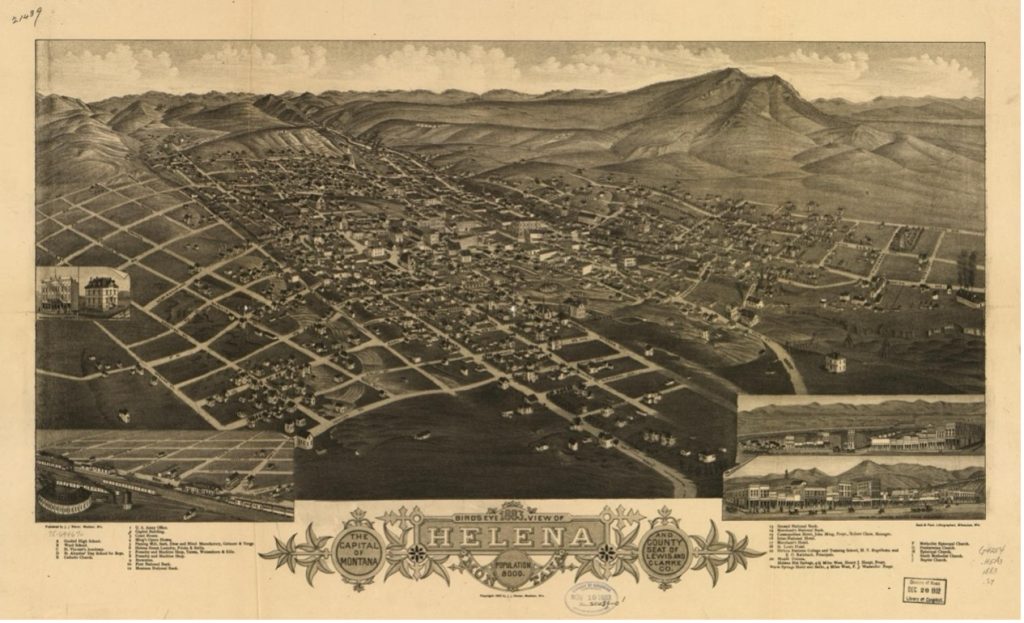

Bird’s Eye view of Helena, Montana in 1883. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/75694670/.

In February 1892, the local Helena newspaper reported that Porter had arrived at the town’s Ming’s Opera House in grand style:

“Arrayed in a dress of spotless white, with feather trimmings to match, pink slippers and flesh-colored stockings, a Gainsborough hat on her head, and the rest of her garments in keeping, Mrs. Mary Porter, the well-known colored member of the demi-monde, presented herself in front of Ming’s Opera House on Friday night with a female companion” (The Daily Independent [DI], February 7, 1892).

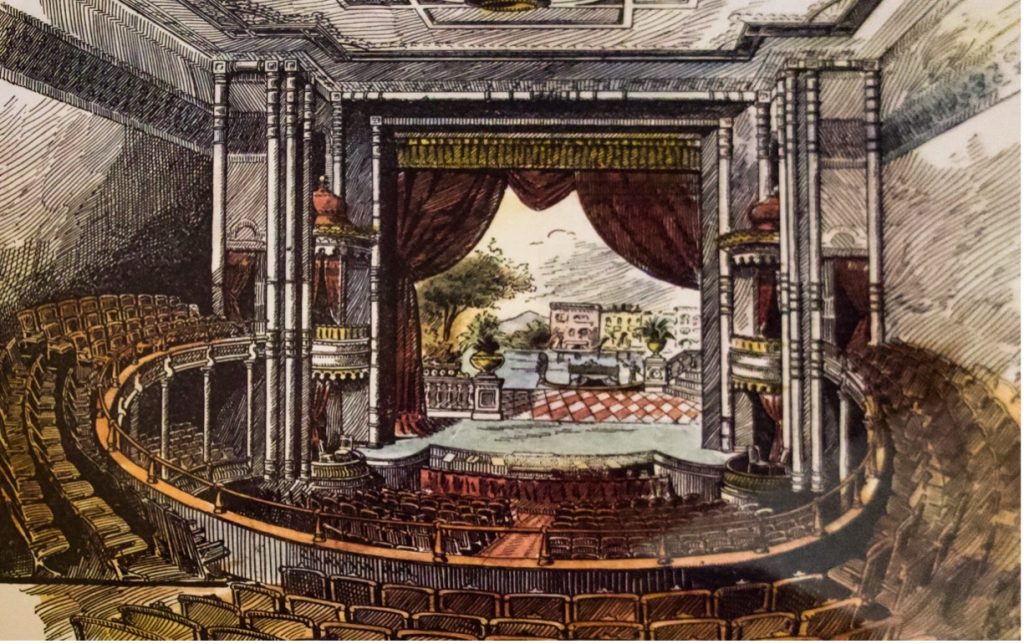

Interior of Ming’s Opera House, 1883

Porter had come to see Pygmalion and Galatea, a comic play by W. S. Gilbert (of Gilbert and Sullivan fame). But Porter was refused entry. The doorman said Porter was “dressed loud,” and that she had “walked in the aisles while a performance was in progress” (DI, November 8, 1893). In response, Porter did what few women, and even fewer Black women, could afford to do in 1890s Montana. She sued.

Porter sued Francis Pope, the lessee of Ming’s Opera House, for racial discrimination and defamation. Porter v. Pope made it to district court, where the judge ruled that “people who behave in an unbecoming manner can be refused entrance” (DI, November 8, 1893).

Porter lost the case.

This court decision set into stone a trend that had been plaguing Helena’s musical world since Porter arrived in 1880: the idea that “loudness” was a moral issue.

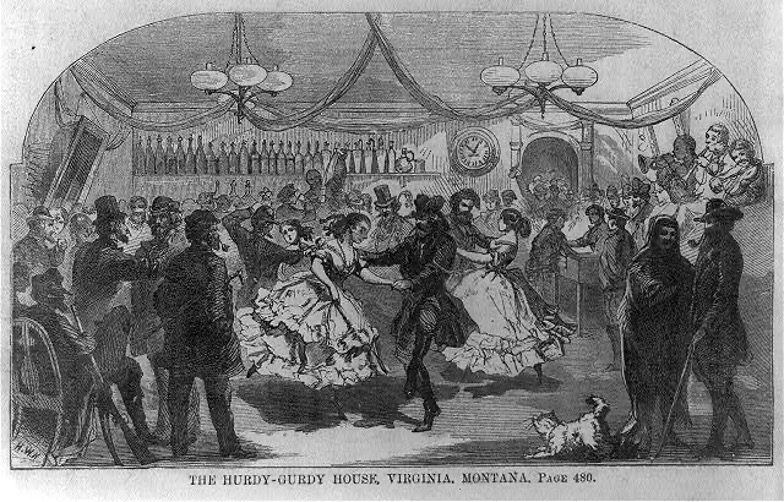

It’s an ironic decision, because really the soundscape of Helena had never been quiet. By 1880, the town throbbed with sound. There were at least three major theaters, which each put on a unique bill of acts most evenings. Theaters advertised with brass bands performing excerpts on street corners. Meanwhile, concert saloons (saloons with a corner stage and a seedy reputation) featured small instrumental combos, usually with violin, banjo, and trumpet.

Image of Hurdy Gurdy House from nearby Virginia City, Montana, which features the classic concert saloon instrument combination. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004679247/.

Long before the incident with Ming’s, Porter was embedded in the town’s concert saloon and theater scene. After a stint as a clerk at a Helena hotel, she began a far more lucrative business: being a “box girl” at Josephine “Chicago Joe” Hensley’s Coliseum Variety Theater (DI, January 18, 1890). Porter’s job as a box girl meant she was a server in one of the Theater’s twenty private boxes. She poured men drinks and, behind the privacy of the boxes’ velvet curtains, plied the other parts of her trade.

When she no longer worked as a box girl, she became a dancing girl at Levi Larkins’s Bucket of Blood saloon. Larkins would become the first Black man elected to Helena’s board of aldermen. After a nasty dispute, Porter tried to shoot him on the dance floor. Before their altercation, though, Porter’s life at the Bucket of Blood was soundtracked by songs by Stephen Foster and “Old Essence of Virginny,” popular on-stage minstrelsy ballads. Newspapers reported on the Bucket of Blood as a violent frontier saloon. But most nights, it was just a place where residents of Helena’s multiracial vice district came together with drink and song. For Porter, as for many women in Helena’s vice district, music was more than background noise. It was her livelihood.

The incident at Ming’s Opera House in 1892 wasn’t the first time Porter was in the papers. Nor would it be the last. Her name appeared again and again in the newspapers: accused of “disturbing the peace,” of “conduct that shocked the denizens of Helena’s Clore Street” (DI, April 27, 1899). But buried among those reports is a moment of stillness.

Upon being jailed for disturbing the peace in Billings, Montana in 1909, Porter asked for a violin. Her request shows another side of Helena’s sound: one where the music she made wasn’t for entertainment, but instead an act of care for herself.

I imagine her fingers tracing the same melodies she might have heard from Helena’s theaters or boardinghouses: a waltz, a hymn, maybe a folk tune from Kentucky, where she was born. The sound would have filled the cold air of her jail cell, wood against stone, string against skin.

That is also the sound of the West: intimate, improvised, human. It wasn’t the silence of a lone cowboy’s guitar, but the murmur of women like Porter making their living through sound. We talk about music in the American West as though it were all ragtime pianos or Aaron Copland’s prairies. But it also lived in jail cells, in boardinghouses, in the back rooms of brothels. It lived in the everyday gestures of people whose stories didn’t make it into concert programs.

Siriana Lundgren (she/her) is a PhD candidate in Historical Musicology at Harvard University and a proud Montanan. Her research investigates the sounds of vice throughout the western United States, examining how working-class women used music as a tool of power.

Learn more about this topic:

Learn more about migration westward by African Americans

Learn more about the history of Helena, Montana

Learn more about the history of early American variety theater