It is difficult to imagine the world of video games without Mario. With the release of Mario Kart World in June 2025 and big-budget films like The Super Mario Bros. Movie (2023), Mario is clearly firmly rooted in contemporary popular culture. The point in history when Mario captured the hearts, minds, and ears of North American video game players can be traced to a specific moment and, indeed, a specific device: the Nintendo Entertainment System.

2025 marks the fortieth anniversary of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES for short) in North America. It is because of this device that consumers in North America could take Mario home, solidifying the mustachioed, blue overalls–wearing plumber among the most iconic video game characters. Yet there was a time when Mario’s place in the video game industry was not so certain.

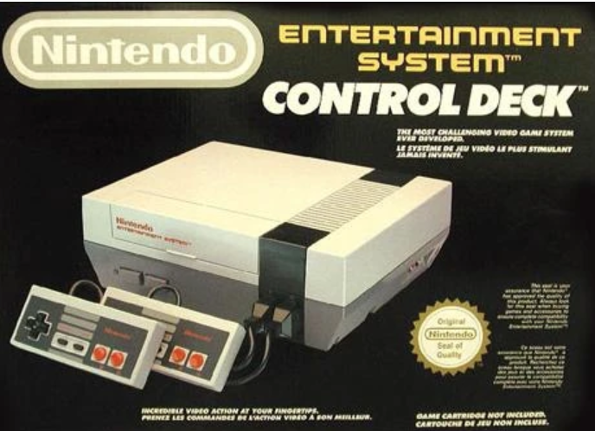

The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), Nintendo’s debut home console in North America

In the early 1980s, the video game industry was thriving. Consoles such as the Atari 2600 (1977), the Magnavox Odyssey 2 (1978), and the Intellivision (1979) were selling in the millions. Realizing how profitable video games could be, many electronics manufacturers turned to video game development. Yet problems were stirring as more and more companies saturated the market. Many games lacked originality in their design; there were, for example, countless clones of the hit game Pong (1972). Plus, many companies released games prematurely due to unrealistic development timelines. Consumers of home console video games were getting sick of playing the same undercooked games over and over.

In December 1982, Atari, the leading game manufacturer in North America, projected that its profits would grow 50 percent in the following year. But in 1983, video game stocks plummeted. So began a crushing blow to the game industry in North America, wiping out most console manufacturers. Mattel Electronics reported losses of up to $100 million at the beginning of 1983, which increased to $300 million by the end of 1984. Atari’s losses reached $500 million by the end of 1983.

Across the Pacific, Nintendo, a Japanese game manufacturer, had released its own console, the Family Computer (Famicom for short), in July 1983 to great success in the Japanese market. But company president Hiroshi Yamauchi wanted to expand the company and sell their console in the United States. Selling the console in North America at this turbulent time would be a major challenge, to say the least. The company needed a strategy.

Yaauchi’s strategy involved rebranding the Famicom as a toy. So, Nintendo renamed its console. Worried that the phrase “video game” might turn consumers off, the Famicom was not a video game console, but an entertainment system—the Nintendo Entertainment System.

The original North American trailer for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)

If Nintendo had any chance of selling the NES in North America, the company needed to make games specifically for the console. And they needed games that were original and avoided the monotonous design that had left the console market stale. To keep the NES from being viewed as a video game console, designers Gunpei Yokoi and Shigeru Miyamoto developed two accessories: the R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy), which users would play with in the games Stack-Up and Gyromite, and the NES Zapper, an electronic light gun used to shoot ducks in the game Duck Hunt.

Nintendo’s console not only had to look better than its competitors; it had to sound better, too. The sound chip in the Atari 2600 console could generate only two pitches. The ColecoVision (1982), which used the SN76489 sound chip, had just three tone generators and one noise generator.

“Menu Music” from E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) for the Atari 2600

Yukio Kaneoka, a sound engineer at Nintendo, developed a sound chip specifically for the NES. His chip, the RP2A03, boasted five sound channels. These included two square-wave channels (for melodies); a triangle-wave channel (for bass lines); a white noise channel (for drum parts); and a sample channel (for sound effects). The variety of sound channels afforded Nintendo’s composers the chance to make more complex video game music. The console’s launch game, Duck Hunt, was immensely popular, but there was another game that stood out to consumers: Super Mario Bros.

The RP2A03 in the NES motherboard

“Menu Music” from Duck Hunt (1984)

Super Mario Bros. was not like any other game. It had a vividly colorful world with various locations for players to explore: a vibrant overworld, a dark, cavernous underworld, underwater areas, and fiery castles. For this game, Nintendo’s staff composer Koji Kondo wrote the score.

In looking at the game world’s bright blue sky, Kondo went to work drafting the theme music. However, when he shared his music with Nintendo’s designers, they all felt the result “wasn’t quite right.” While Kondo’s music matched the game’s colorful visuals, it didn’t capture the energetic, frantic rhythm of Mario as a character. After all, Super Mario Bros. was a game all about jumping. Kondo went back to the drawing board. Thinking of the character’s rhythm, Kondo programmed a swung drumbeat using the NES’s white noise channel. He then began improvising melodies that would eventually become the different sections of the iconic “Overworld” theme.

The “Overworld” theme from Super Mario Bros. (1985)

Kondo went on to compose music for other areas of the game. He wrote a funky disco bassline for the underworld, a waltz for the water areas, and a dissonant and stress-inducing piece for the castles where players fight the evil King Koopa (a.k.a. Bowser). Kondo composed a total of less than three minutes of music for the game. However, it remains some of the best-known video game music, heard throughout dozens of Nintendo games and extending beyond the television speakers into America’s cultural landscape.

During its lifetime, the NES sold 34 million units in North America and over 60 million worldwide. Despite the precarity of the home console industry in North America, Nintendo prevailed through the creative and collaborative efforts of its team members. Thanks to the technological innovations of the Nintendo Entertainment System, forty years later, we still have Mario, we still have Nintendo, and as evident in the trailer for the upcoming blockbuster The Super Mario Galaxy Movie, we still have the music.

Theatrical trailer for the upcoming film The Super Mario Galaxy Movie

James Heazlewood-Dale is a scholar and Grammy-nominated bassist hailing from Melbourne, Australia. He migrated to Boston to pursue studies in jazz double bass at the prestigious Berklee College of Music and the New England Conservatory, where he received full scholarships, and has since shared the stage with world-renowned artists including Jacob Collier, Zakir Hussain, and Terence Blanchard. He completed his PhD at Brandeis University in 2024, writing his dissertation on the intersection of video game music and jazz. His work can be read in Jazz and Culture and Environmental Humanities and the Video Game, and he appears as a scholarly guest in Adam Neely’s acclaimed video essay “The Nintendo-fication of Jazz.”

Learn more about this topic:

Andrew Schartmann, Analyzing NES Music: Harmony, Form, and the Art of Technological Constraint

Karen M. Cook, William Gibbons, and Fanny Rebillard, eds., Global Histories of Video Game Music Technology

Kenneth McAlpine, Bits and Pieces: A History of Chiptunes